There is one thing you need to know to know my dad.

Besides the Warren Beatty story. But that's for another time.

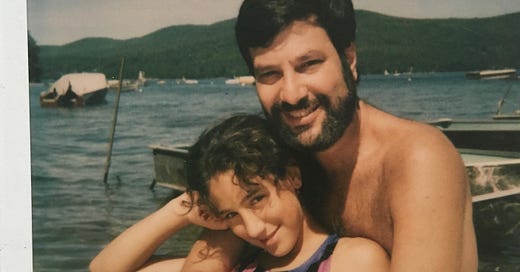

I was ten when my parents split up.

At the time, it was rare enough that my teacher sat me down with the one other girl in my class with divorced parents, hoping we could be friends.

I was sad, briefly, if memory serves, but soon I remember saying things like, “it’s not that bad. I get two birthday cakes.”

Maybe I meant it. Maybe I just said it enough times until I meant it.

My dad moved to the city and every Wednesday he came back up to bring my brother and me to Cook’s in Mamaroneck for hot dogs and and chocolate chip mint on a cone (or lemon sherbet with rainbow sprinkles, depending) and give us four quarters each for the arcade. Or more accurately, he’d give us each a dollar, and then we had to track down the “change guy” and his apron full of quarters. If you were a Cook’s regular like we were, you knew he generally hid out somewhere between the pinball machines in the back and the bathrooms.

But the weekends we spent at his midtown apartment, those were the best.

We always did something special that my suburban friends could only have dreamed of, even if it was a fairly ordinary kind of special: Screening old monster movies at The Film Forum, or nabbing tickets to a festival of Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin silents, which was accompanied by a live pianist and absolutely the coolest thing I could have imagined at the time. Swiveling in the ratty chairs at the old Mike’s Luncheonette counter slurping Chocolate Egg Creams. Playing catch where East 51st Street dead-ends between Beekman Place and the River, right in the street! People-watching in the cosmetic aisles of Bloomingdale’s, as he pointed out all the ladies in furs and strappy heels and full faces of makeup, who would never go there without dressing up. Watching jugglers and street musicians in Central Park. Learning how to hail cabs and put tokens in the subway turnstiles.

I especially loved sitting on his tiny terrace with my brother and making up backstories for the people we spotted in the windows across the courtyard. Like the lady who vacuumed in her bra, or the man who grabbed his wife’s butt when she was rooting through the fridge. Though arguably our favorite across-the-way neighbor was “the dead guy” — someone who seemingly collapsed to the ground…before surprising us by doing leg lifts. The only plausible explanation was, certainly, that he was an exercise-loving zombie.

We played Bruce Springsteen records and old Broadway soundtracks on the requisite fancy record player owned by all single guys in the 80s.

We grilled hot dogs on the illegal hibachi.

We drank soda.

We read books quietly, all together on the same couch.

We stayed up late enough to watch Saturday Night Live — or at least to Weekend Update—hoping to see the Coneheads or the Cheeseburger Cheeseburger Cheeseburger guys or if we were SUPER lucky, Mr. Bill, before it was time to blow up the air mattresses in the living room and go to bed.

But what I valued even more than any of those things is that on the days I wasn’t with him, we talked on the phone. Nearly every single day, without fail.

In high school, he bought me my own phone (that would be a landline, younger friends), a serious indulgence at the time; but this way we could speak any time and without interruption.

When I was old enough to work minimum wage jobs scooping ice cream or selling candy by the pound, he called me at the store during every shift—much to the dismay of whatever manager would have to suggest that maybe I could limit the personal calls during work hours?

When I went to college, he called me every night, if only for 5 seconds to say, “just saying hi, Lizzie.” I never minded at all.

I was about 12 the night my dad my took a woman named Amye with an E at the end on a first date at my favorite special Italian restaurant in the neighborhood. My brother and I hung back at the apartment, eating crackers in his bed (something I am still apologizing for!) and watching TV far past our bedtimes.

Ah, GenX—the generation of kids who stayed home alone at night with no neighbor parents to get all sanctimonious about it, because they were doing it too.

After dinner, he told Amye he had to stop home to grab a jacket before heading back out for a drink.

Grab a jacket she thought. Sure. Okay.

But he was grabbing a jacket. He was a gentleman.

On the elevator ride up, he told her, “there’s something important you need to know about me—I have two kids and they’re here at the apartment this weekend. They don’t live with me full-time, but I am a full-time dad.”

That one sentence is all you need to know to know my dad.

It wasn’t for years—decades—that I recognized how extraordinary a statement it was, especially at a time just after first-wave feminism, and long before fathers started pushing back against strangers at the park cooing how absolutely adorable it was to see them “playing mommy” or “babysitting” their kids.

There’s a lot more of course, but that’s one story I’ve been telling since forever, to try and sum up my dad in a single sentence

I think he’d be the first to tell you: he’s still a full-time dad.

And he still calls me almost every day, without fail.

Lovely memories. Happy Father’s Day, Paul. Liz, your father once told me as I was looking out my windows in Yeadon, as a hopeful, romantic teenager, waiting for my boyfriend to drive by, “ a watched pot never boils”, and to this day if I use that expression, I think of him!

I dunno, Liz. Walter’s has THE hot dogs in Mamaroneck.